🎙️ The oldest song

An attempted reconstruction of an ancient work of music. Starting from a 3400 year old clay tablet, how much is guesswork?

🪶 The oldest surviving musical composition, and why it doesn’t sound like this. Or this. 🪶

Disclaimer: this is not a peer-reviewed article. Its purpose is to entertain and educate, not to consolidate research. I have made a reasonable effort to ensure accuracy and fair representation of the facts, but material below should not be relied upon as a primary reference.

Image attributions can be found at the end of the article.

Ancient music

In the Middle Eastern Bronze Age, the 14th century BCE, four hundred years before King David supposedly played his ‘secret chord’, music was flourishing.

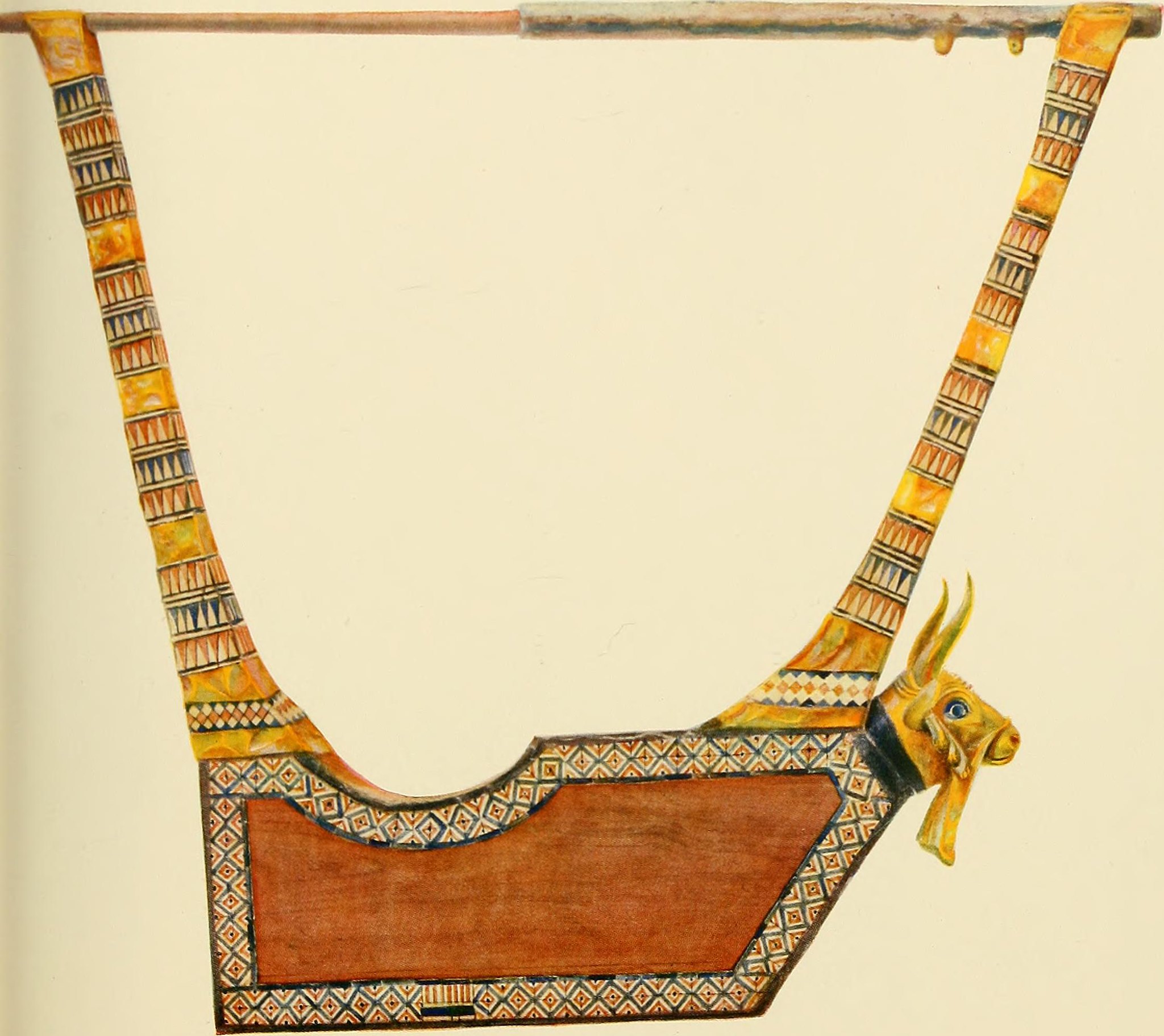

Art from the era depicts musicians in high society, with an extensive range of instruments: drums, cymbals, pipes, horns, lyres and harps, even lutes. Scholars write complex treatises on musical theory, kings and queens are given ornate instruments as gifts, and children of the literate classes get musical education.

Society as whole enjoyed music as part of everyday life; song and dance underpinned social occasions, ceremonies, and worship in many of the same ways it still does. Presumably there were also musicians who played for art’s sake.

It’s hardly a unique feature of this period, by the way. Archaeological evidence shows that most of this was still true another 1000 years before, and no doubt still further given the diversity of music on record.

But let’s stay at this particular date, around 1400 BCE.

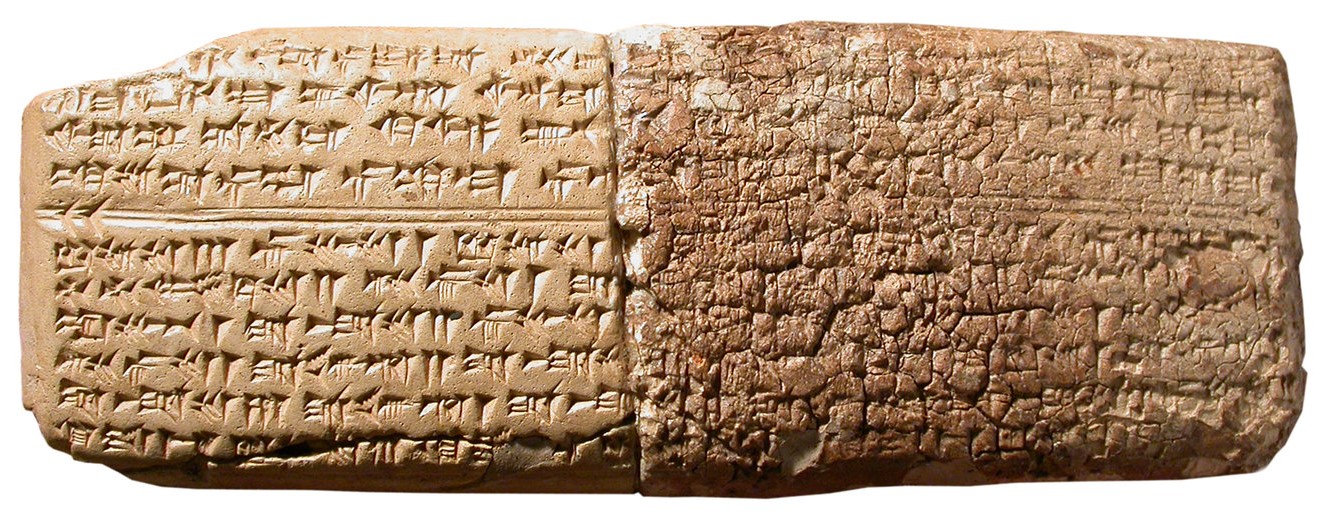

One specific tablet from this time, a text found in northern coastal Syria, has been identified as the oldest surviving musical composition. It is known as Hurrian hymn h.6. Researchers have of course been inspired to recreate the music, but there simply isn’t enough to go on, and attempts so far have been… speculative at best.

Notwithstanding the challenge, I couldn’t resist taking a look myself, to see what problems are encountered when interpreting the text, and perhaps use some musical intuition to navigate the possibilities. In this article I will:

- Introduce the tablet and its inscriptions.

- Bring in other tablets as context for the composition.

- Summarize what is known and unknown about the tablet’s music.

- Evaluate previous interpretations, and share my own.

Follow along and enjoy this three-and-a-half-millennia-old work. You be the judge of whether any of the interpretations land anywhere near the truth.

The tablet

Location

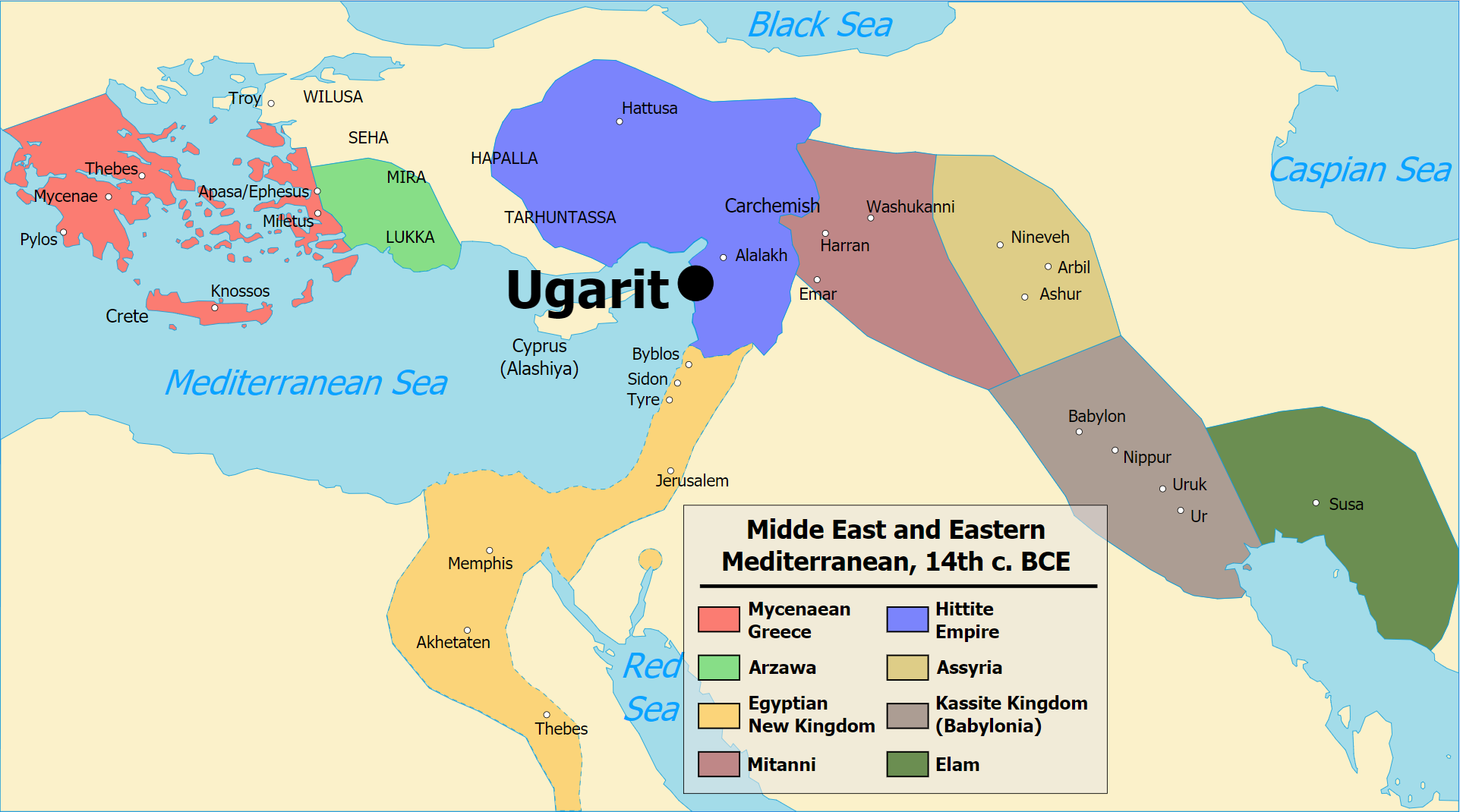

The tablet containing h.6 was found in excavations of Ugarit, which by the 14th century BCE was an important and cosmopolitan port city on the Mediterranean coast.

Ugarit is at the north end of the Syrian coastal plain, which is bounded by Mount Lebanon to the south and a smaller mountain range to the east. Access to the continent was through a nearby pass, with the then-declining kingdom of Mitanni found inland in Upper Mesopotamia, and the Hittite Empire to the north in Anatolia.

Ugarit had remained largely autonomous and non-militaristic, instead growing wealthy through trade. However, around this time, the Hittites expanded southward and absorbed the city and its lands as a vassal state

They were no stranger to visitors, though.

Being at the crossroads of north-south and land-sea trade routes, Ugarit accommodated people with all sorts of languages and religions.

Our hymn is one of 36 hymns found at the site in the Hurrian language, and is the most complete of the collection. It is addressed to Nikkal, a cross-cultural goddess of fruit and fertility, mother of the sun god, and wife of the moon god.

Linguistics

Many languages are known to have passed through Ugarit because of its connections with the outside world:

- Akkadian (Semitic)

- the lingua franca of the ancient Middle East

- Hurrian (isolate)

- principal language of Mitanni and the Hurrians

- Hittite and Luwian (Indo-European)

- languages of the Hittite Empire

- Egyptian (a distinct branch of the Afroasiatic family)

- used in the Egyptian New Kingdom

- Cypro-Minoan (undeciphered)

- from maritime trade with Cyprus

- Ugaritic (Semitic) – a dialect of Amorite

- the native language of the city of Ugarit

- Sumerian (isolate, extinct)

- a classical language used by scholars and priests

The tablet actually contains two of these – while the hymn is written in Hurrian, the musical terms and scribe’s imprint are Akkadian.

Both are written phonetically, using Hittite cuneiform syllables:

b | p | d | t | g | k | ḫ | l | m | n | r | š | z | |

-a | 𒁀 | 𒉺 | 𒁕 | 𒋫 | 𒂵 | 𒅗 | 𒄩 | 𒆷 | 𒈠 | 𒈾 | 𒊏 | 𒊭 | 𒍝 |

-e | 𒁁 | 𒁉 | 𒁲 | 𒋼 | 𒄀 | 𒆠 | 𒄭 | 𒇷 | 𒈨 | 𒉈 | 𒊑 | 𒊺 | 𒍣 |

-i | 𒁉 | 𒋾 | 𒈪 | 𒉌 | 𒅆 | ||||||||

-u | 𒁍 | 𒁺 | 𒌅 | 𒄖 | 𒆪 | 𒄷 | 𒇻 | 𒈬 | 𒉡 | 𒊒 | 𒋗 | 𒍪 | |

a- | 𒀊 | 𒀜 | 𒀝 | 𒄴 | 𒀠 | 𒄠 | 𒀭 | 𒅈 | 𒀸 | 𒊍 | |||

e- | 𒅁 | 𒀉 | 𒅅 | 𒂖 | 𒅎 | 𒂗 | 𒅕 | 𒌍 | 𒄑 | ||||

i- | 𒅋 | 𒅔 | 𒅖 | ||||||||||

u- | 𒌒 | 𒌓 | 𒊌 | 𒌌 | 𒌝 | 𒌦 | 𒌨 | 𒍑 | 𒊻 | ||||

| a | e | i | u | ya | wa | wi | |

| 𒀀 | 𒂊 | 𒄿 | 𒌑 | 𒅀 | 𒉿 | 𒃾 |

Other syllables exist. Some are alternative signs for those listed above, but there are also closed syllables (consonant–vowel–consonant). Cuneiform is versatile and can be read in many ways. But most of the transliteration that follows uses only the ones shown.

Here I’m using a font (Ullikummi) that displays variants of cuneiform glyphs simlar to those used on the tablet.

Cuneiform was already 1000 years old, developed by Sumerians in a entirely unrelated language. Akkadian used the Sumerian symbols both logographically (dubbed Sumerograms, in much the same way as Chinese characters are used for Japanese kanji) and phonetically, using quite a few possible readings.

Then, when Hittites adopted the script in their language, they in turn used Akkadian words logographically (Akkadograms), as well as the old Sumerograms and phonetic readings. Combined with flexible spelling, handwriting variation, and damage, it becomes a bit of a challenge to read in the modern era.

Hurrian is, believe it or not, from a fourth(!) unrelated branch of linguistic evolution. Fortunately this hymn is spelled phonetically, so transcription is relatively simple once the groundwork of determining the correct syllabary has been done.

You can have a go at it yourself using the table above and photograph below.

Transcription

Since I am not in any way an Assyriologist, I won’t go into any further detail on deciphering cuneiform. Let’s just pick up where experts left off (refer to Wikipedia for the important names on this topic).

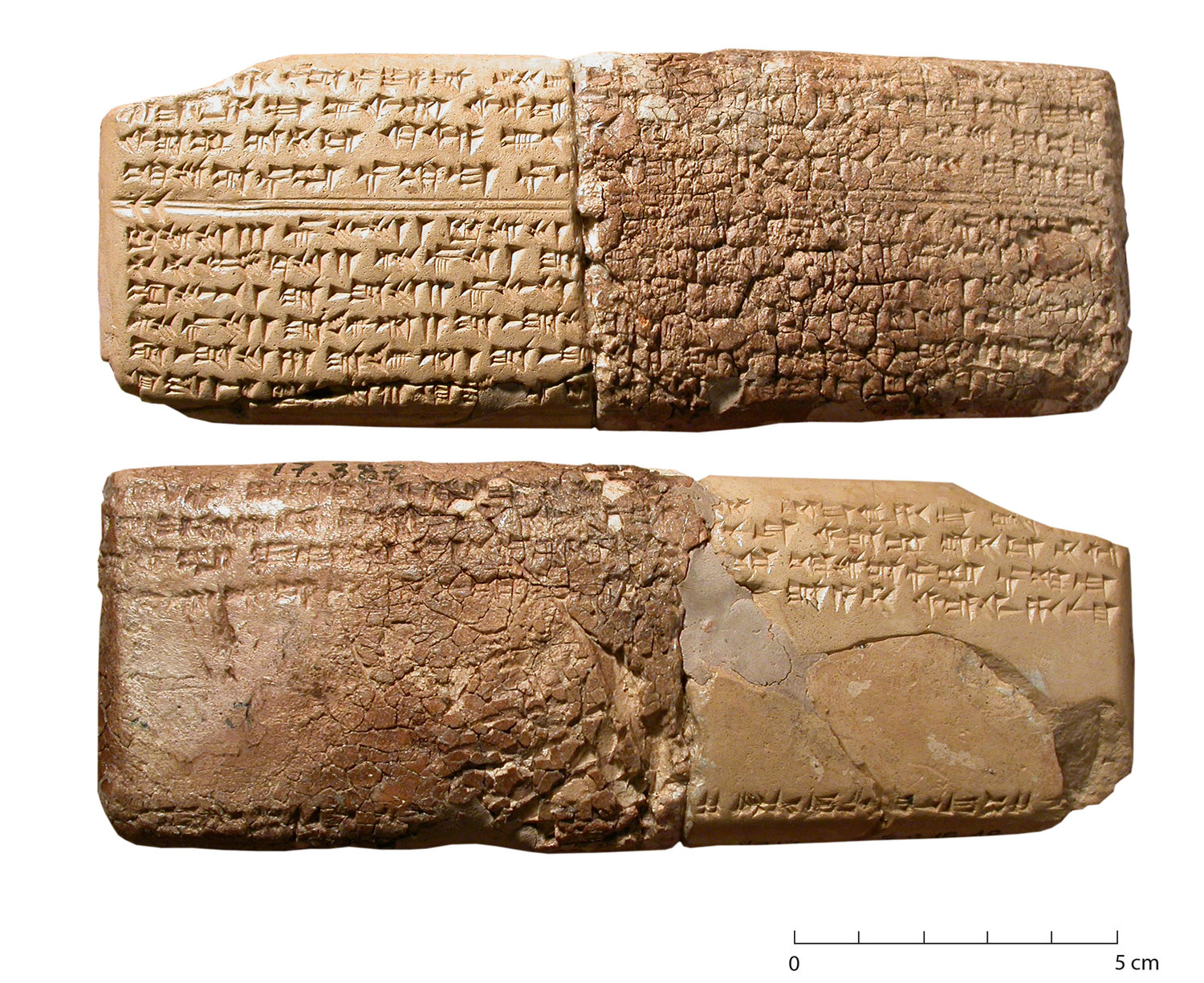

H.6 was first transcribed in the 1960s following the tablets’ discovery, but a more complete version is presented here, Theo Krispijn’s work of 2000 (recorded at this webpage).

Left-aligned text corresponds to the front of the tablet, and right-aligned the reverse. Lines wrap round from the front to the back over the edge, and successive lines begin with a repeat of the last few words of the previous line.

| 𒄩𒀸𒋫𒉌𒅀𒊭 𒍣𒌑𒂊 𒅆𒉡𒋼 𒍪𒌅𒊑𒅀 𒌑𒁍𒂵𒊏[𒀜/𒀝] 𒄷 |

| ḫa-aš-ta-ni-ya-ša zi-ú-e ši-nu-te zu-tu-ri-ya ú-pu-ga-ra-[at/ak] ḫu- |

| 𒌨𒉌 𒋫𒊭𒀠 𒆠𒅋𒆷 𒈬𒇷 𒅆𒅁𒊑 𒄷𒈠𒊒𒄩𒀜 𒌑𒉿𒊑 |

| -ur-ni ta-ša-al ki-il-la mu-li ši-ip-ri ḫu-ma-ru-ḫa-at ú-wa-ri |

| 𒄷𒈠𒊒𒄩𒀜 𒌑𒉿𒊑 𒉿𒀭𒁕𒉌𒋫 𒌑𒆪𒊑 𒆪𒌨𒆪𒌨𒋫 𒄿𒊭𒀠𒆷 |

| ḫu-ma-ru-ḫa-at ú-wa-ri wa-an-da-ni-ta ú-ku-ri ku-ur-ku-ur-ta i-ša-al-la |

| 𒌑𒆷𒇷 𒆏𒄀 𒌑𒇷𒌑𒄀 𒅆𒊑𒀉 𒌑?𒉡𒋗 𒉿𒊭𒀠 𒋫𒋾𒅁 𒋾𒅆𒀀 |

| ú-la-li kab-gi ú-li-ú-gi ši-ri-it ú?-nu-šu wa-ša-al ta-ti-ib ti-ši-a |

| 𒉿𒊭𒀠 𒋫𒋾𒅁 𒁲𒅆𒀀 𒌑𒉡𒌌 𒆏𒅆𒇷 𒌑𒉡𒌌𒀠 𒀝𒇷 𒊭𒄠𒊭𒄠𒈨𒉌 |

| wa-ša-al ta-ti-ib di-ši-ya ú-nu-ul kab-ši-li ú-nu-ul-al ak-li ša-am-ša-am-me-ni |

| 𒋫𒇷𒅋 𒊌𒆷𒀠 𒌅𒉡𒉌𒋫 𒊓?XXXX𒅗 𒅗𒇷𒋫𒉌𒅋 𒉌𒅗𒆷 |

| ta-li-il uk-la-al tu-nu-ni-ta sa?-x-x-x-x-ka ka-li-ta-ni-il ni-ka-la |

| 𒅗𒇷𒋫𒉌𒅋 𒉌𒅗𒆷 𒉌𒄷𒊏𒊭𒀠 𒄩𒈾 𒄩𒉡𒋼𒋾 𒀜𒋫𒅀𒀸𒋫𒀠 |

| ka-li-ta-ni-il ni-ka-la ni-ḫ[u]-r[a]-ša-al ḫa-na ḫa-nu-te-ti at-ta-ya-aš-ta-al |

| 𒀀𒋻𒊑 𒄷𒂊𒋾 𒄩𒉡𒅗 X𒍪 XXX𒀸𒊭𒀀𒋾 𒉿𒂊𒉿 𒄩𒉡𒆪 |

| a-tar-ri ḫu-e-ti ḫa-nu-ka x-zu [x-x-x-a]š-ša-a-ti wa-e-wa ḫa-nu-ku |

| ════𒌋𒌋═════════════════════════════════════════════════𒌋𒌋════ |

| 𒆏𒇷𒋼 𒐈 𒅕𒁍𒋼 𒁹 𒆏𒇷𒋼 𒐈 𒊭𒄴𒊑 𒁹 𒋾𒋾𒈪𒊬𒋼 𒌋 𒍑𒋫𒈠𒀀𒊑 |

| kab-li-te 3 ir-bu-te 1 kab-li-te 3 ša-aḫ-ri 1 ti-ti-mi-šar-te 10 uš-ta-ma-a-ri |

| 𒋾𒋾𒈪𒊬𒋼 𒈫 𒍣𒅕𒋼 𒁹 𒊭𒄴𒊑 𒈫 𒊭𒀸𒊭𒋼 𒈫 𒅕𒁍𒋼 𒈫 |

| ti-ti-mi-šar-te 2 zi-ir-te 1 ša-[a]ḫ-ri 2 ša-aš-ša-te 2 ir-bu-te 2 |

| 𒌝𒁍𒁁 𒁹 𒊭𒀸𒊭𒋼 𒈫 𒅕𒁍𒋼 X 𒈾𒀜𒆏𒇷 𒁹 𒋾𒋻𒆏𒇷 𒁹 𒋾𒋾𒈪𒊬𒋼 𒐼 |

| um-bu-be 1 ša-aš-ša-te 2 ir-bu-te x na-ad-kab-li 1 ti-tar-kab-li 1 ti-ti-mi-šar-te 4 |

| 𒍣𒅕𒋼 𒁹 𒊭𒄴𒊑 𒈫 𒊭𒀸𒊭𒋼 𒐼 𒅕𒁍𒋼 𒁹 𒈾𒀜𒆏𒇷 𒁹 𒊭𒄴𒊑 𒁹 |

| zi-ir-te 1 ša-aḫ-ri 2 ša-aš-ša-te 4 ir-bu-te 1 na-ad-kab-li 1 ša-aḫ-ri 1 |

| 𒊭𒀸𒊭𒋼 𒐼 𒊭𒄴𒊑 𒁹 𒊭𒀸𒊭𒋼 𒈫 𒊭𒄴𒊑 𒁹 𒊭𒀸𒊭𒋼 𒈫 𒅕𒁍𒋼 𒈫 |

| ša-aš-ša-te 4 ša-aḫ-ri 1 ša-aš-ša-te 2 ša-aḫ-ri 1 ša-aš-ša-te 2 ir-bu-te 2 |

| 𒆠𒀉𒈨 𒈫 𒆏𒇷𒋼 𒐈 𒆠𒀉𒈨 𒁹 𒆏𒇷𒋼 𒐼 𒆠𒀉𒈨 𒁹 𒆏𒇷𒋼 𒈫 |

| ki-it-me 2 kab-li-te 3 ki-it-m[e] 1 kab-li-te 4 ki-it-me 1 kab-li-te 2 |

| [𒀭𒉡]𒌑 𒍝𒄠𒈠𒀸 𒊭 𒉌𒀉𒄒𒇷 𒍝𒇻𒍣 XXXXXX 𒋗 𒁹𒄠𒈬𒊏𒁉 |

| [an-nu]-ú za-am-ma-rum ša ni-id-kib-li za-l[u]-z[i] xxxxxx šu Iam-mu-ra-bi |

| This is a song in nīd qablim, a zaluzi [by …, scribed] by Ammurabi |

Context for the notation

The intervals

To the untrained eye, this doesn’t look much like music. However, there’s something special about those words in the second part.

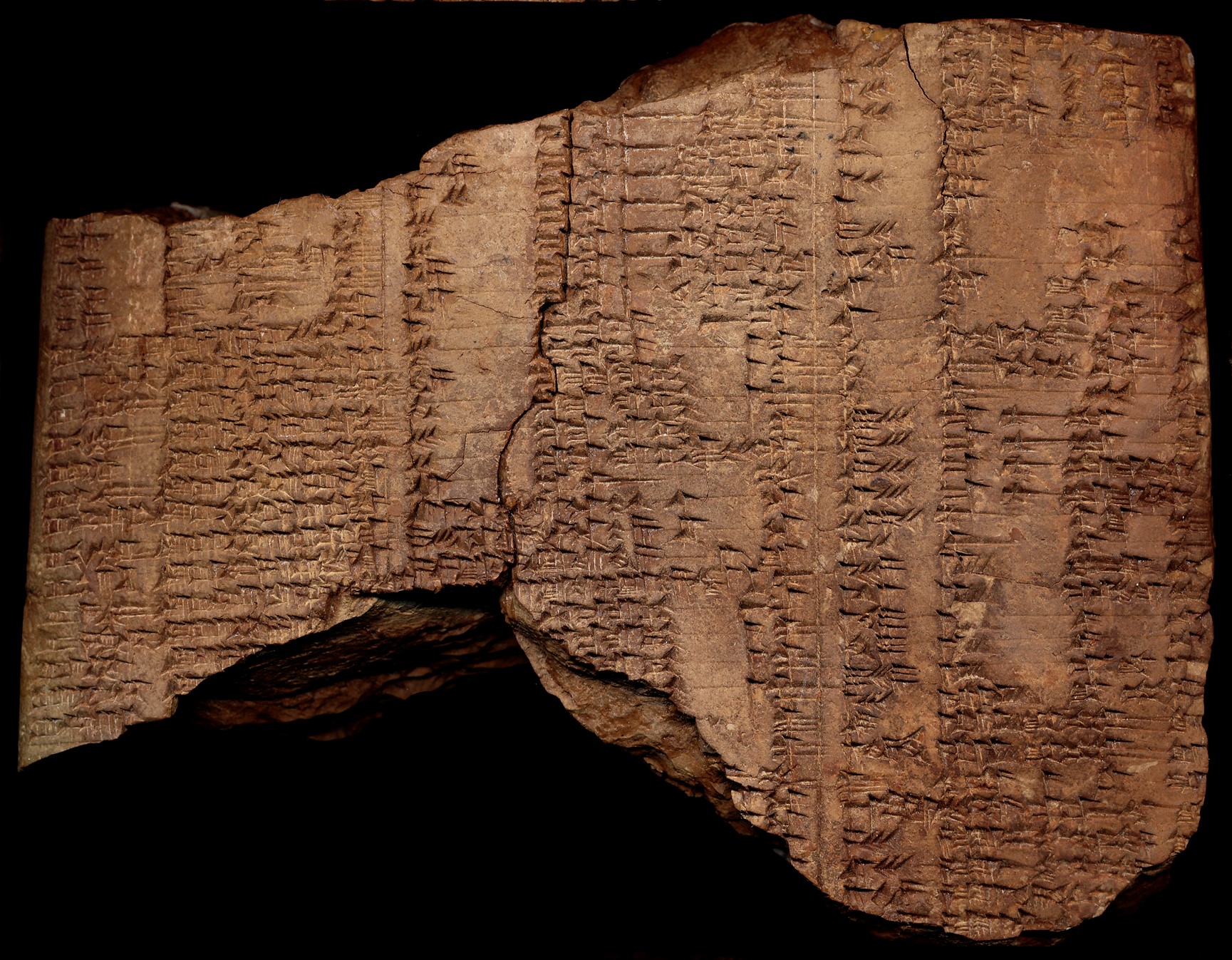

They correspond to words from another tablet, CBS 10996. This tablet isn’t exactly from the same place (it was found in Nippur, Lower Mesopotamia) but the terminology pops up in quite a few texts over a wide area and timespan.

From these sources we know that the terms refer to pairs of strings on a lyre. Originally Akkadian with meanings such as “middle”, “fourth”, and “opening”, they are Hurrianized in this text and others, without equivalent translation.

| Akkadian term | Hurrian term | Cuneiform in h.6 | Strings |

|---|---|---|---|

| nīš tuḫri | (nīš-tuḫ-ri) | (𒌋𒌋𒃮𒊑) | 1–5 |

| šērum | ša-aḫ-ri | 𒊭𒄴𒊑 | 7–5 |

| išartum | (i-šar-te) | (𒄿𒊬𒋼) | 2–6 |

| šalšatum | ša-aš-ša-te | 𒊭𒀸𒊭𒋼 | 1–6 |

| embūbum | um-bu-be | 𒌝𒁍𒁁 | 3–7 |

| rebûtum | ir-bu-te | 𒅕𒁍𒋼 | 2–7 |

| nīd qablim | na-ad-kab-li | 𒈾𒀜𒆏𒇷 | 4–1 |

| isqum | (eš-gi) | (𒌍𒄀) | 1–3 |

| qablītum | kab-li-te | 𒆏𒇷𒋼 | 5–2 |

| titur qablītum | ti-tar-kab-li | 𒋾𒋻𒆏𒇷 | 2–4 |

| kitmum | ki-it-me | 𒆠𒀉𒈨 | 6–3 |

| titur išartum | ti-ti-mi-šar-te | 𒋾𒋾𒈪𒊬𒋼 | 3–5 |

| pītum | (pi-te?) | (𒁉𒋼) | 7–4 |

| serdûm | zi-ir-te | 𒍣𒅕𒋼 | 4–6 |

Parentheses ( ) indicate that the term is not clearly found in h.6; reconstruction where possible is from the other hymn fragments.

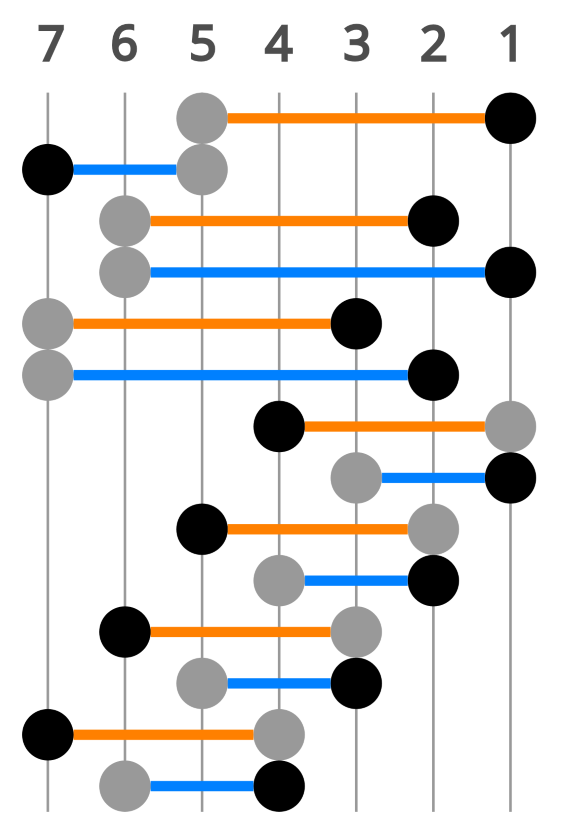

The intervals span 3, 4, 5, or 6 strings. Those that span 4 or 5 (shown in orange below) are often referred to as the ‘primary’ intervals

The strings 6 and 7 are in fact referred to in CBS 10996 as “4th rear” and “3rd rear”, implying two more strings (8 and 9). Another text (UET VII 126) confirms this with a listing of all nine strings in order.

We might as well stick to numbers from now on, so the hymn’s notation becomes:

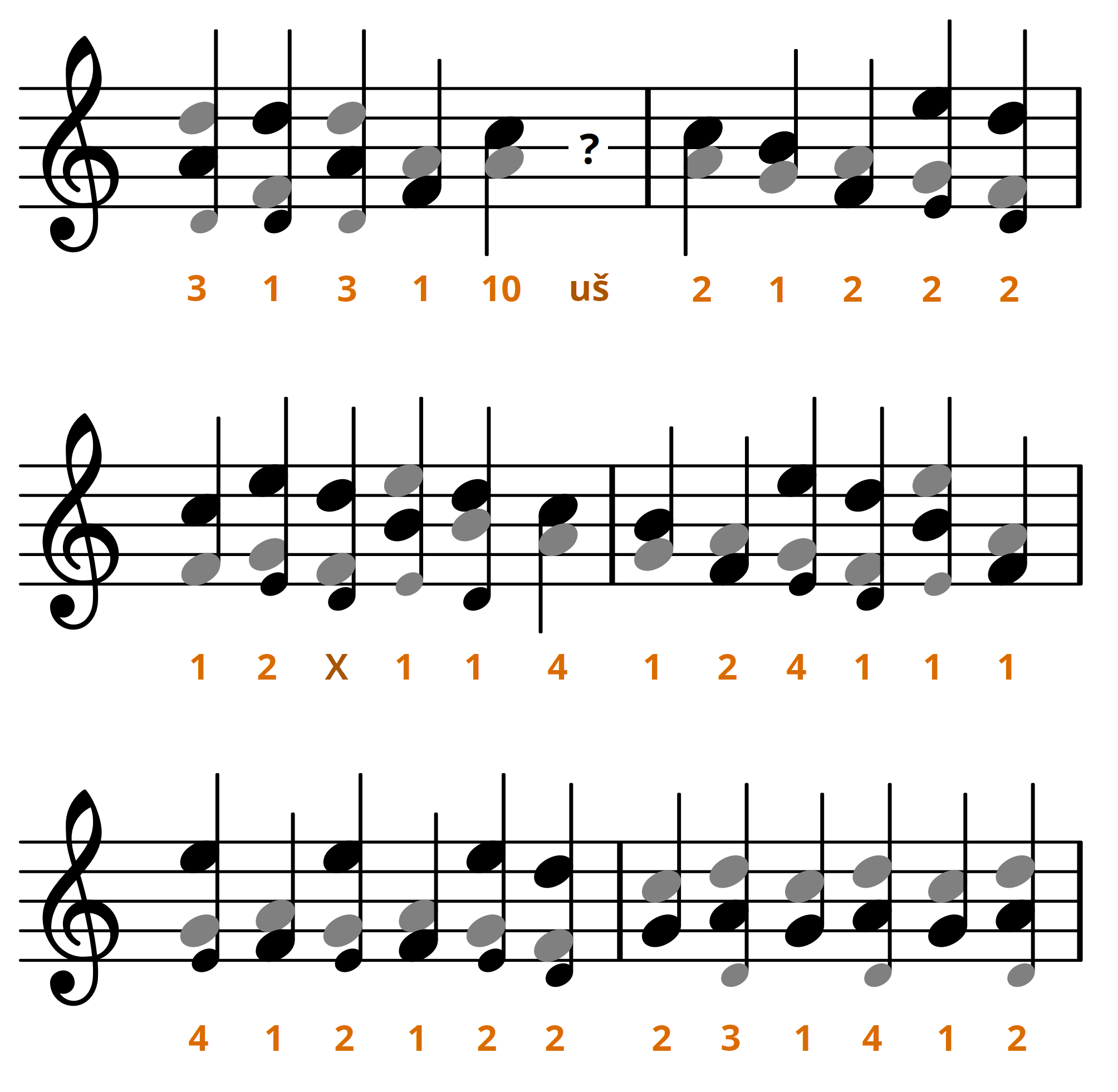

5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 10 | uš-ta-ma-a-ri | |||

2 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 5 | |||||||||

3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||||||||

3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | X | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

|

|

7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 5 | ||||||||

4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 1 |

|

|

6 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 5 | ||||||||

1 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

|

|

6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||||||||

6 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

|

|

3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||

So far, so good, but a long way from playable music.

In the immediate aftermath the harp’s discovery, that was all there was to go on, but researchers were of course keen to interpret the work into sonic reality. With so little context, this was mostly an exercise in composing by numbers, not true reconstruction.

Today we can do better thanks to other tablets, though there is still a lot of wiggle room. The next sure step we can take is determining how the strings should sound.

The strings

For this, the crucial text is UET VII 74, which gives instructions for taking a nine-string lyre (or harp) between seven tuning systems. Each instruction translates as:

“If the instrument is in [tuning], the [interval] is unclear. Tighten [string], and the instrument is now in [next tuning].”

Tuning | Unclear interval | Tighten | |

|---|---|---|---|

išartum | qablītum | 5–2 | 5 |

qablītum | nīš tuḫri | 1–5 | 1 and 8 |

nīš tuḫri | nīd qablim | 4–1 | 4 |

nīd qablim | pītum | 7–4 | 7 |

pītum | embūbum | 3–7 | 3 |

embūbum | kitmum | 6–3 | 6 |

kitmum | išartum | 2–6 | 2 and 9 |

The tablet also contains the reverse procedure, loosening strings.

From such clear instructions we learn a lot.

- Strings 1 + 8, and 2 + 9, are tuned together.

- The larger numbers were also omitted from CBS 10996.

- They’re probably the same pitches an octave apart.

- There are seven steps inside this octave

- There are seven tunings, forming a cycle.

- The string to be tightened changes in a regular pattern.

- Each tuning is likely to be a scale of unrepeated pitches.

- The ‘unclear’ interval can be tuned into clarity by ear.

- The span of the interval is always 4 or 5 strings.

- It probably means re-tuning a diminished 5th into a perfect 5th.

On the evidence so far, most agree only one possibility reasonably fits: that these tunings are descending diatonic scales, as shown in the animation below. In other words, they have the same structure as the major, natural minor or other modes.

It’s hard to know what absolute pitch they would have tuned to, but I’ve made a tactical choice of using D for string 9 (the lowest string) throughout the cycle.

| Strings | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tuning | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | (9→2) | (8→1) |

išartum | D | E♭ | F | G | A♭ | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | Locrian | Ionian |

qablītum | D | E♭ | F | G | A | B♭ | C | D | E♭ | Phrygian | Lydian |

nīš tuḫri | D | E | F | G | A | B♭ | C | D | E | Aeolian | Locrian |

nīd qablim | D | E | F | G | A | B | C | D | E | Dorian | Phrygian |

pītum | D | E | F♯ | G | A | B | C | D | E | Mixolydian | Aeolian |

embūbum | D | E | F♯ | G | A | B | C♯ | D | E | Ionian | Dorian |

kitmum | D | E | F♯ | G♯ | A | B | C♯ | D | E | Lydian | Mixolydian |

The music

This section deals with the full scope of possible interpretations; for individual examples, see the final section.

What we know

After all that deciphering, where are we? Well, if we’re hoping to perform the hymn as intended by the composer, we are not quite there, but we can:

- Reconstruct a harp or lyre tuned to nīd qablim, and

- Read the word-based notation as a series of string pairs.

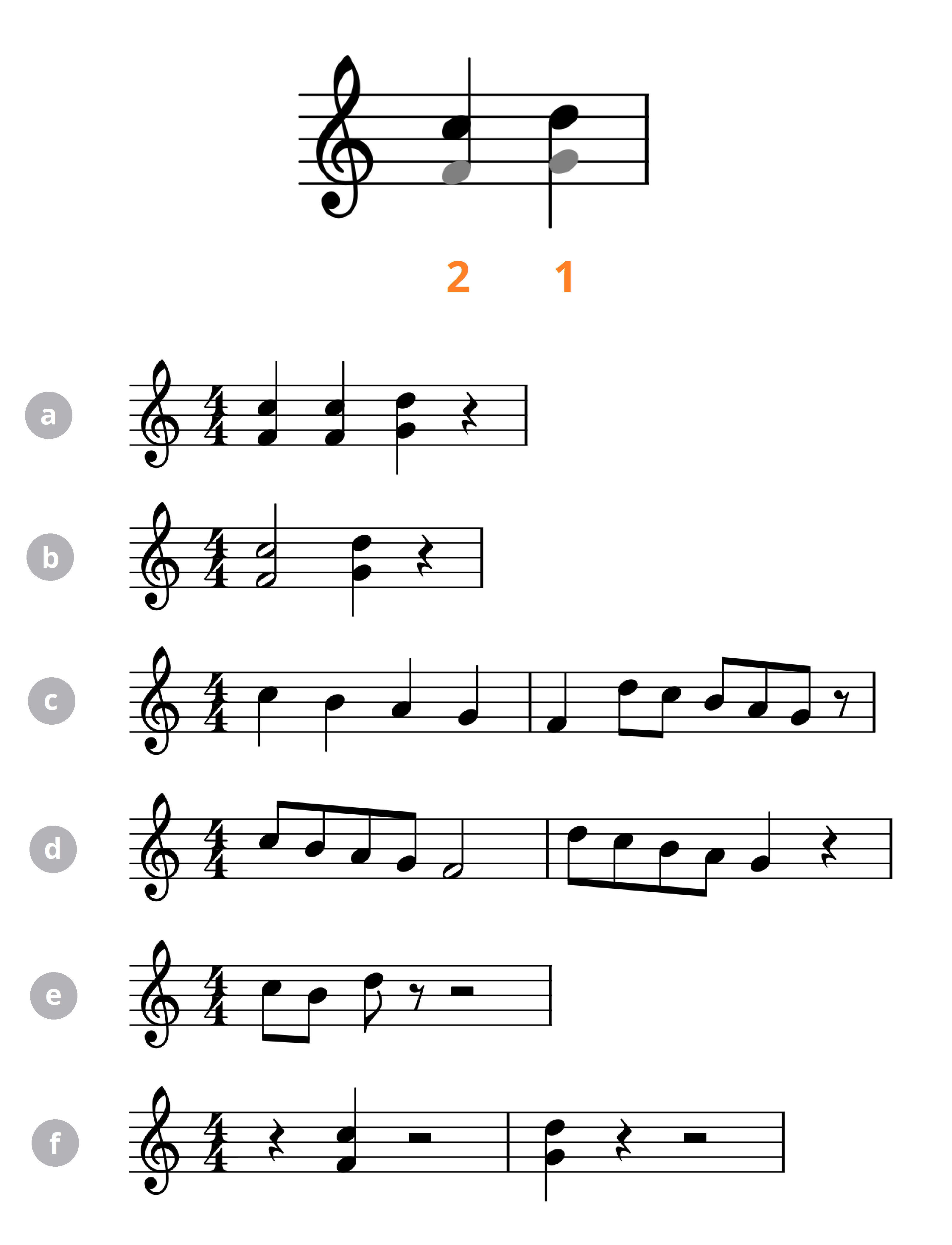

The first listed string of each interval (according to CBS 10996) is coloured black; the second, grey. Whenever string 1 or 2 is present, I’ve added string 8 or 9 with a small notehead.

Numbers under the intervals are the ones found after each word on the tablet, with “uš” standing in for uš-ta-ma-a-ri.

We are still in the dark, however, about a few important things: 3. What does a string pair mean in terms of performance? 4. What do the numbers between words mean? 5. What does uš-ta-ma-a-ri signify? 5. What is the relationship of the music to the text of the hymn?

Unfortunately there are no more magic tablets to help answer these questions; from here on it’s more about codebreaking and musicianship than archaeology.

Daunting, but let’s follow where others have boldly gone before.

What we don’t know

Polyphony

A major source of disagreement is whether the music can have been polyphonic. In other words, would multiple strings ever be played simultaneously?

The argument centres around a lack of evidence for polyphony anywhere in the world until many hundreds if not thousands of years later. Although, with polyphony-capable instruments dating from well before h.6, not to mention playing in groups, there is little evidence to the contrary, either.

After unpitched percussion, the earliest (prehistoric) music would obviously have been monophonic, but had harmony developed by 1400 BCE?

Some scholars (West, Vitale, Dumbrill) take pains to avoid interpreting the string pairs as polyphony; they’d rather read them as a melodic line.

And they do have a point.

If the intervals are harmonic, why are they listed with a mixture of low-string-first and high-string-first in CBS 10996? Even if this isn’t meaningful, it’s odd enough that it begs a different explanation.

However, Michael Levy – not an academic but a musician specializing in ancient lyre – has a different view.

Deriding the “dogma” of musicologists who “have never actually played a lyre”, he makes a compelling counterpoint:

Any ancient musician with any musical imagination, would realize [that] specific notes on either the harp or lyre sound pleasant when played together!

To him it’s mad that, after tuning an instrument with fifths, we say they would not play those fifths in music. Frankly I’m with him.

But then we have to accept only having polyphonic notation. And that the hymn is composed entirely in harmony: not impossible, but it’s a leap some are rightly cautious to take.

Let’s weigh up the possibilities:

Interpretation | Does not explain | Possible answers |

|---|---|---|

simultaneous chord | Why inconsistent string order? | It’s unimportant to be systematic |

The list is systematic, but opaquely so | ||

Why is monophonic notation not used? | The piece is all polyphonic | |

The lyre was not played monophonically | ||

This notation gives the performer some freedom to play monophonically | ||

two-note sequence | Why not just use a single-note notation? | Phrasing is always by pairs of notes |

Why inconsistent string order? | The listed order is the ‘primary orientation’ of the interval | |

Why is only one interval direction listed? | Modifier words might give access to the inverse intervals | |

interval-filling scale | Why inconsistent string order? | The listed order is the ‘primary orientation’ of the interval |

Why is only one interval direction listed? | Modifier words might give access to the inverse intervals |

Purely on its notational merits, I think it’s fair to say that a chord interpretation is the most literal, most complete, and most versatile reading. But it is hardly a concise way to write fast passages.

I also dislike the constraints of these melodic readings, and there are still issues over orientation. But it is a tempting shorthand.

Maybe it’ll be more fruitful to explore those numbers instead…

Rhythm

Since the words give the pitch, that leaves the numbers to perform some other role. (Either that or they also carry melodic meaning with a kind of mixed notation. But it’s hard to see how without overcomplicating matters.)

The only accessible possibility, it seems, is to read the numbers as an indicator of timing, rhythm, duration or similar. If not, then what? Volume? Choreography? I somehow doubt it.

There are a few variants of this idea:

Options a through d are intuitive enough; e uses the numbers to indicate how many notes from the scale should be present, and f (my own invention) uses them as beats of the bar on which to play.

The reader will no doubt be able to think of more.

However, there’s absolutely no guarantee that one of these options is the truth. In fact, they all have such deficiencies that I favour none of them:

- Option a is so rhythmically dull that the suggestion is an insult to our forebears (remember, rhythm predates melody by a long way). Unless, that is, we allow for further interpretation by the lyrist.

- Option b is an improvement, but interpreted this way h.6 sounds random and lacks any overarching structure. Perhaps it is subservient to the sung text?

- Option c is an unappealing and unintuitive way to count, especially when it leads to odd tuplets.

- Option d is innocuous enough (though a tad arbitrary), but suffers from the same ‘random’ feeling as b.

- Option e makes the least sense to me. Who would design a notation like this, reading a scale then discarding half of it?! Particularly when ir-bu-te 1 and ti-tar-kab-li 1 would both just be “string 2”.

- Option f has some interesting properties, and I will give my brainchild a fair hearing. But as with many of these, the 10 in the first line of music causes problems.

In any musical notation, some things are left to be filled in by performers, who are sensitive to the context and conventions in which the work sits and can adapt accordingly.

It may be that the notation is more like a chord sheet, indicating an improvisational framework out of which an arbitrarily complex melody can be plucked. We can only speculate, and it’s safest to do so with small leaps of the imagination rather than large ones.

A guiding principle is whether the result sounds convincing: a human artistic work rather than a jumble of sound. But then again, who’s to say the music was ever any good?

Music and text

Let’s not forget that the major portion of the tablet is not music.

But it is clearly part of the hymn, as sung lyrics or otherwise. If it’s supposed to be sung, we need to discover how the words match to the music.

Maybe the numbers are there to guide this process; rather than defining a rhythm on their own, they might let the natural rhythms of language take melodic shape.

Is there an obvious way this might happen? Perhaps with numbers dictating how many words or syllables to sing?

| Quantity | Value |

|---|---|

| Words | 49+ |

| Syllables | 130+ |

| Intervals | 34 |

| Numbers (sum) | 72+ |

The short answer is no. Word-setting is a notoriously strange marriage between musical and poetic aesthetics, and without a degree of comfort in Hurrian, it’s a tall order to reverse engineer.

Though some researchers have picked a syllabic scheme and merrily laid out the song in full, it is doubtful whether these capture the composer’s intention. I will not try anything myself: I feel embarrassingly underqualified.

One word in particular stands out, though

At the end of the first line of music we see the word uš-ta-ma-a-ri. it literally translates as “not for singing”. But does this refer to one interval, the whole line, or the whole hymn? Is the instrument or the voice that should be silent? Or is it more of a stylistic marking (like staccato or piano in more modern music)?

It’s yet another complication left to guesswork.

Overall, then, we’re not going to get much more help from the tablet. Extracting a satisfactory piece of music will continue to be a process of inspiration, execution, and evaluation.

Interpretations

Now it’s finally time to see some versions of the piece in its entirety.

Legal considerations: In order to avoid navigating what is copyrighted and what is public domain, and to maintain consistency between works, I’ve chosen to create automated equivalents following the rules above, thus reproducing the guiding concepts of each work rather than the work itself. The differences do not affect my evaluations.

In the light of UET VII 74, interpretations based on ascending tunings are now known to be incorrect. This includes those of David Wulstan (1971), Anne Draffkorn Kilmer (1974), and Marcelle Duchesne-Guillemin (1977), who are otherwise credited with the major early work in this area).

I have chosen not to display these versions. Generally speaking, they are superseded by later readings with the correct tonality.

The video game Civilization V, notable for a soundtrack inspired by early music from the regions of its playable powers, seems to have missed this fact in using Kilmer’s version.

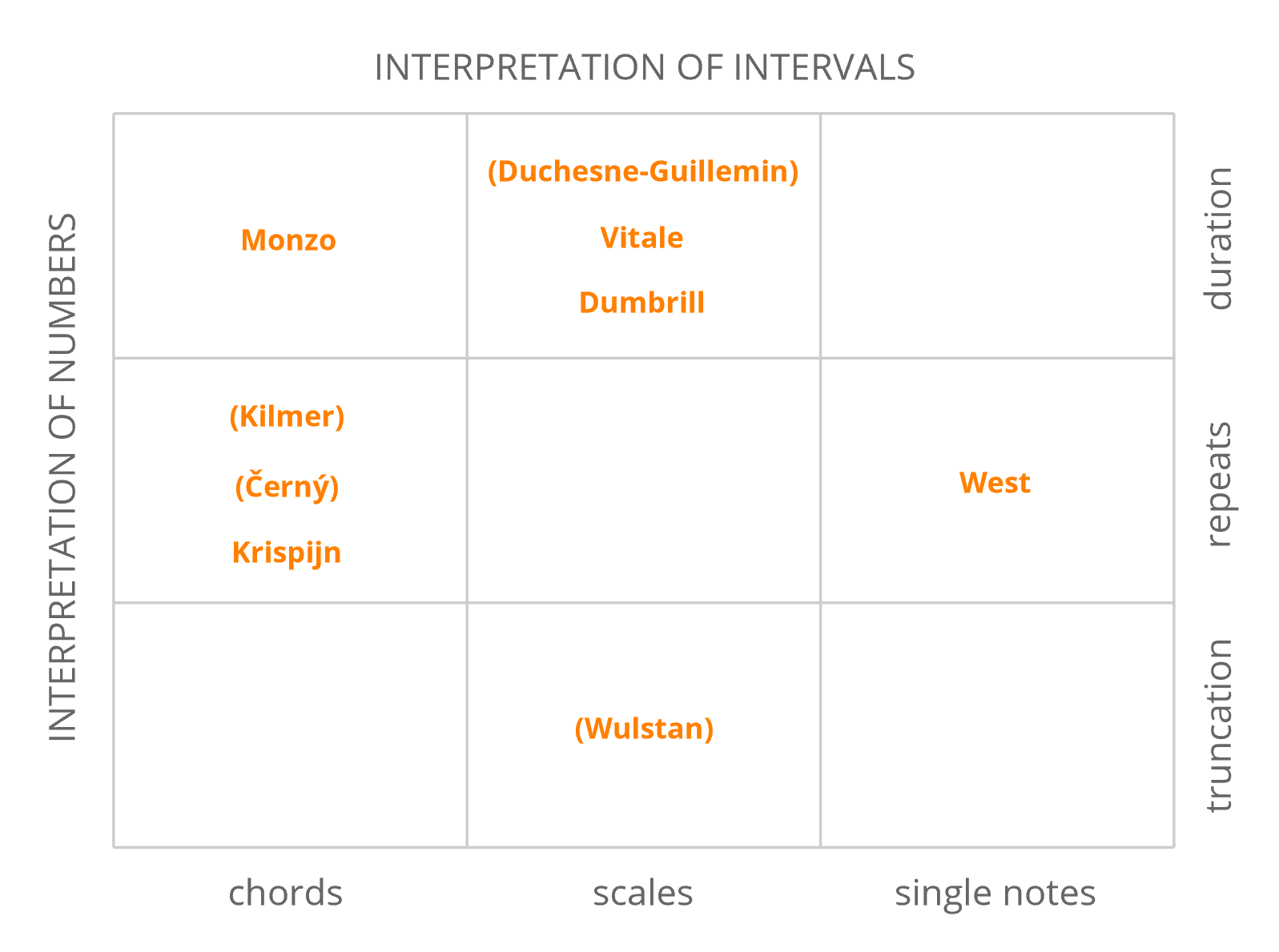

Of the published arrangements of h.6 that I’ve seen or heard, all are constructed from the ideas laid out earlier. The various combinations can be summarized in a matrix:

For example, Anglo-French archaeomusicologist Richard Dumbrill opts to render all the primary intervals as descending scales of five notes, and all the secondary ones as three. He uses the numbers to determine the duration of each bar’s final note (rhythm interpretation d).

Verdict: in his academic books and videos, Dumbrill is extremely rigorous, but this arrangement cuts a few corners. Intervals are flipped for artificial internal consistency at the expense of the notation itself, and rhythmic decisions are heavily subjective.

This represents an admirable attempt to get into the mindset of the composer and recreate something worthwhile. It’s a pleasant tune, but not convincingly authentic.

Melody (aesthetics) ★★★☆☆ (justification) ★★☆☆☆

Rhythm (aesthetics) ★★★☆☆ (justification) ★☆☆☆☆

Structure (aesthetics) ★★★☆☆

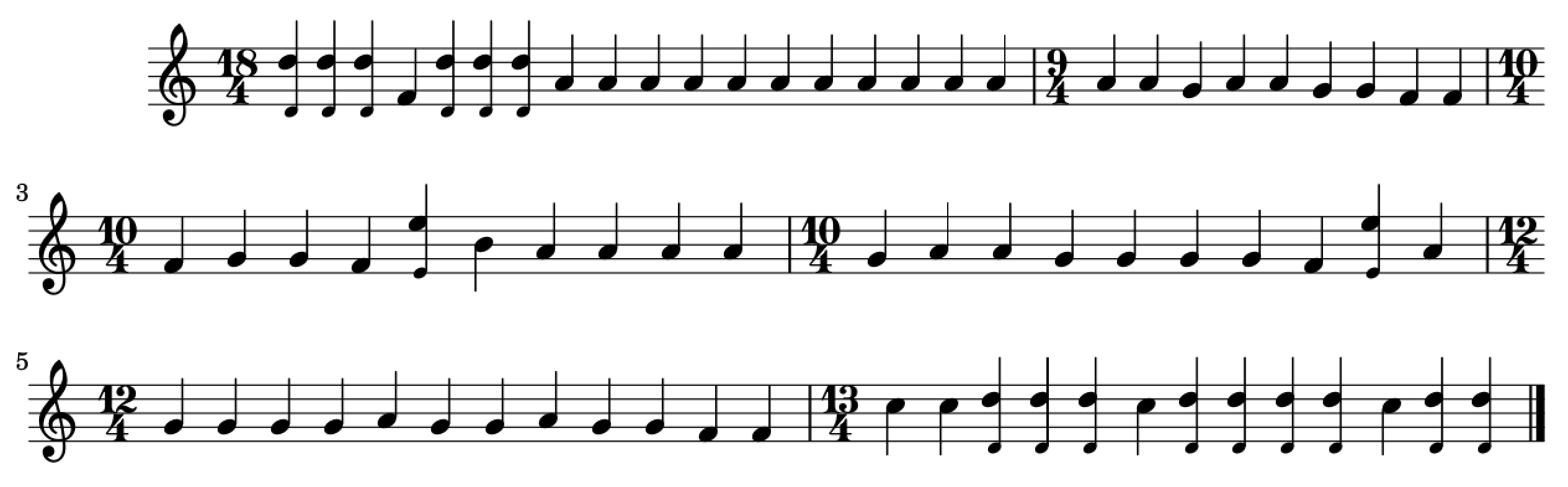

Meanwhile, eminent classicist Martin Litchfield West chooses to ignore the first string from every interval, and uses the numbers as indications to repeat (rhythm interpretation a).

Verdict: West takes a minimal, soft-touch approach. The result falls short of real music, but there are no big decisions to find fault with, except perhaps discarding half of each interval. It’s an arrangement content to remain far from the original rather than risk straying further away.

Melody (aesthetics) ★☆☆☆☆ (justification) ★★★☆☆

Rhythm (aesthetics) ★☆☆☆☆ (justification) ★★★★☆

Structure (aesthetics) ★☆☆☆☆

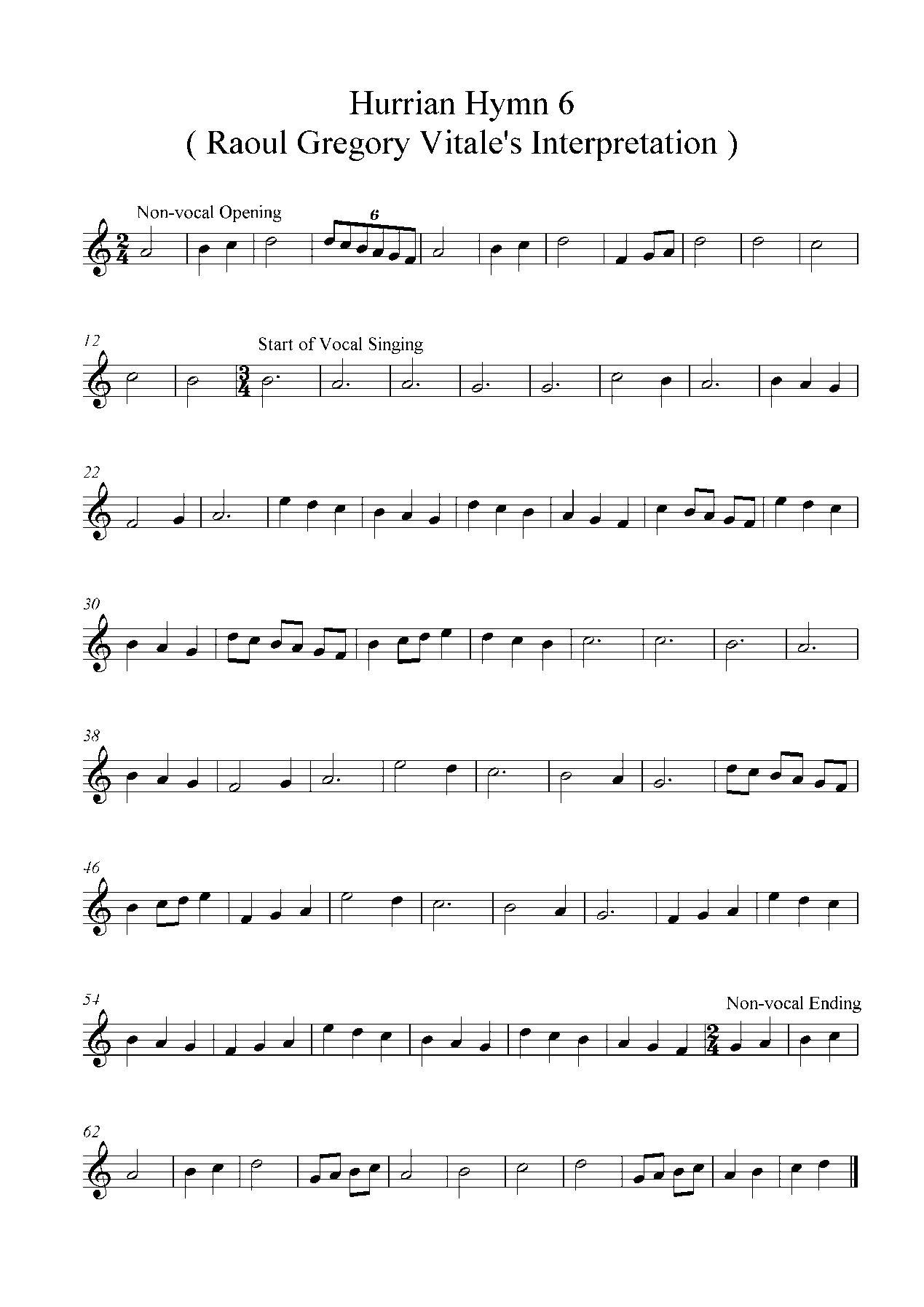

Italo-Syrian archaeomusicologist Raoul Gregory Vitale, born less than 10km from Ugarit, has every reason to add his own thoughts. And indeed he does, using rhythm interpretation c and unmodified scales:

Verdict: Vitale makes no adjustment to the intervals in CBS 10996, simply filling each of them into a monophonic scale in the orientation listed. Rhythmically, however, the idea of stretching each scale by a factor of its accompanying number is novel but a stretch in itself.

Melody (aesthetics) ★★☆☆☆ (justification) ★★★★☆

Rhythm (aesthetics) ★★☆☆☆ (justification) ★★☆☆☆

Structure (aesthetics) ★★☆☆☆

American composer Joe Monzo posted this message on an discussion board in 2000. His version uses plain chords and rhythm interpretation b.

Verdict: As a passion project, Monzo has gone for a fairly straightforward interpretation. Issues of polyphony aside, why wouldn’t this be correct? It’s not the most beautiful, though.

Melody (aesthetics) ★☆☆☆☆ (justification) ★★★★☆

Rhythm (aesthetics) ★☆☆☆☆ (justification) ★★★★☆

Structure (aesthetics) ★☆☆☆☆

Theo Krispijn, the academic who not only transcribed h.6 in the form shown earlier but also gave its most complete translation, has produced a linguistically sensitive arrangement with a simple chords-and-repeats reading of the tablet.

Verdict: Reminiscent of medieval plainsong, Krispijn’s version uses rests to help phrase the otherwise dull rhythms borne of rhythmic interpretation a. In a religious context, this is believable. But is it genuine?

Melody (aesthetics) ★★★☆☆ (justification) ★★★★☆

Rhythm (aesthetics) ★★★☆☆ (justification) ★★★☆☆

Structure (aesthetics) ★★★☆☆

My version

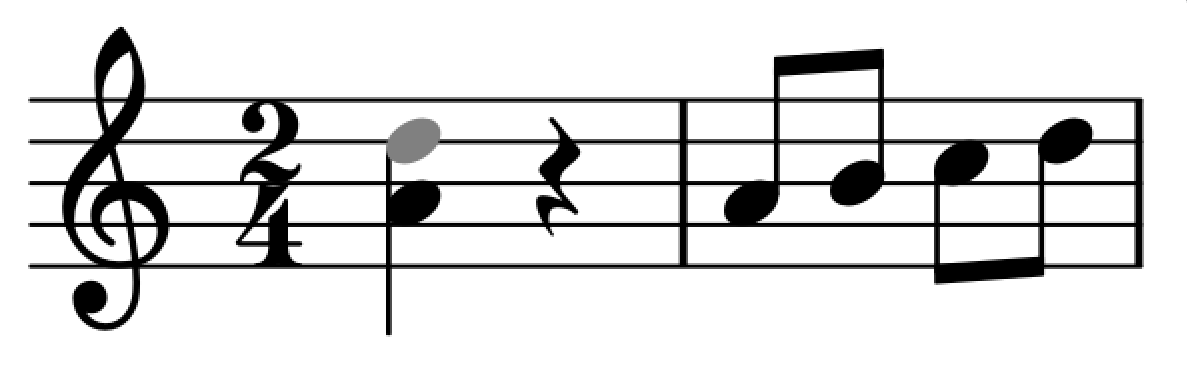

I might as well put forward a version of my own.

I’ve taken rhythm interpretation f, which interprets the numbers as beats in 4/4 time, along with unmodified intervals as chords. To make this work I only had to resolve one issue, interpreting the number 10 (with uš-ta-ma-a-ri) figuratively, as a pause before.

Verdict: It’s hard to be objective about my own work. However, it must be said this is a simple, readable, and intuitive idea. Musically speaking, the piece emerges with a persistent trochaic pulse, and some pleasing aspects of structure.

Personally, though, I dislike the occasional missing downbeats, and the ending is a little abrupt. There’s also a general lack of flow if lyrics were to be superimposed. These shortcomings are enough to leave me thinking I’m not on the money. But perhaps with further development…

Melody (aesthetics) ★★★☆☆ (justification) ★★★★☆

Rhythm (aesthetics) ★★★☆☆ (justification) ★★★☆☆

Piece as a whole ★★★☆☆

Closing thoughts

As it stands, I don’t believe any of these.

Do I think it’s possible to reconstruct the original without more tablets for context? Yes. But will we know when we do? Well, that depends on the music.

One day a dedicated scholar may test a new idea and find it was Greensleeves all along. Or at least, something that sounds so good it has to be right. Alternatively, it could just be so unfamiliar in construction – or just bad – that we unwittingly reject the real version.

Of course, there’s a non-zero chance these are all wrong due to transcription errors: one or more of the intervals or numbers might have been read wrongly. Through no fault of the transcriber, mind. Some things simply get lost between scribing and reading. There’s 3400 years’ worth of damage, after all.

If a musical idea is strong enough we may be able to deduce if the transcription is correct. But in the worst case, hidden errors may complicate and distort our musical reconstructions.

And that’s assuming our friend Ammurabi the scribe wrote it down properly!

Because of all these factors, this is a low-information problem. Such things call for Bayesian thinking.

We can’t expect any single measure of authenticity to dominate and win the argument once and for all. Instead, we need to look for the arrangement that is reasonable from many perspectives.

The simpler the interpretation, the more likely it is to match the one used in 1400 BCE. Likewise, the more musical it is, the more likely it is to have been composed in the first place.

We want both. And other considerations might include how lyre-friendly the music is, and how well it fits with the lyrics.

Overwhelmingly, however, one criterion seems to have muscled its way to the front of the queue: polyphony.

As mentioned earlier, the most direct reading of CBS 10996 is to play two strings simultaneously. This interpretation therefore scores highly on one Bayesian metric.

But this is often dismissed, tempered by a criterion of historical continuity.

Based on the known history of music, there is a higher prior probability that three-thousand-year-old music would be monophonic than polyphonic. But is it a strong prior?

Now, I am the proud owner of a cheap children’s harp. Having played with it for many hours I, like Michael Levy, find it incomprehensible that any musician (ancient or modern) would constrain their playing to one-string-at-a-time. It’s an instrument on which polyphony is so easy it happens by accident!

Leaving my feelings aside, though, I have to say that it seems skepticism over polyphony has unduly become an aversion. There’s a well-known adage that “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence”; moreover, it is unclear what greater evidence we are waiting for. Are these tablets not likely to form part of a future exhibit on early polyphony?

My inexpert opinion is that while, yes, it would be easier to accept a monophonic piece of music, the simplicity of reading CBS 10996 as chords should at least equal this factor in importance.

Next steps

And that’s where I’ll leave this story for now.

If and when I revisit this, it will be because I want to try out some more possible interpretations. I’m reluctant to tinker aimlessly with complicated ideas (it’s not very Bayesian). But there are plenty of untapped simple ones to be found. For example, the numbers could indicate pre-defined patterns to play on each interval, like ballet positions or tones in Mandarin.

If you’re interested in exploring more ancient music, the most famous example is the Seikilos epitaph, from around 100 CE. It’s in great condition and the musical notation is well known, so there’s been no problem performing it. Between you and me though, I prefer something with a bit more mystery, even if it can’t yet be solved.

Thank you for joining me on this adventure in information; I look forward to another.

If you would like to reach me with a comment or request, please use the contact form.

Image attributions

(see terms of use)

Banners. (Portions from photographs of h.6 by Françoise Ernst-Pradal via Sam Mirelman):

> Portion not subject to my copyright; refer to original work.

> Portion not subject to my copyright; refer to original work.

Musical score. Original work h6 Intervals by William Fletcher, CC BY 4.0 made using this Python script and the abjad library

1. Photograph by Carrole Raddato reproduced under CC BY-SA 2.0

2. Portion of photograph of h.6 by Françoise Ernst-Pradal via Sam Mirelman

3. Modified from original plot by Alexikoua under CC BY-SA 4.0. Derivative work Middle East in 14th century BCE by William Fletcher, CC BY-SA 4.0

4. Photograph by Jiří Suchomel shared under CC BY-NC 2.0

5. Photograph of h.6 by Françoise Ernst-Pradal via Sam Mirelman

6. Portion of photograph of CBS 10996 by CDLI staff / Penn Museum

7. Original work Lyre Intervals by William Fletcher, CC BY 4.0

8. Photograph of an illustration from “Ur excavations” (1900), contributed by Umass Amherst Libraries to The Commons on Flickr

9. _Original work Lyre Tunings by William Fletcher, CC BY 4.0 made using this Python script and the manim library

10. Original work h6 Intervals by William Fletcher, CC BY 4.0 made using this Python script and the abjad library

11. Image by José-Manuel Benito Álvarez reproduced under CC BY-SA 2.5

12. Original work Chord and scale by William Fletcher, CC BY 4.0 made using this Python script and the abjad library

13. Original work Interval rhythms by William Fletcher, CC BY 4.0 made using this Python script and the abjad library

14. Image by Luis Miguel Bugallo Sánchez, in the public domain

15. Original work Interpretations matrix by William Fletcher, CC BY 4.0

16. Arrangement following Richard Dumbrill’s process, made using this Python script and the abjad library

17. Arrangement following Martin Litchfield West’s process, made using this Python script and the abjad library

18. Arrangement by Raoul Vitale provided by Rami Vitale and reproduced under CC BY-SA 3.0

19. Arrangement following Joe Monzo’s process, made using this Python script and the abjad library

20. Arrangement following Theo Krispijn’s process, made using this Python script and the abjad library

21. Original work h6 beat interpretation by William Fletcher, CC BY 4.0 made using this Python script and the abjad library